“HONOR THE DEAD BY HELPING THE LIVING”

Vietnam War POWs Gather,

Remember at Nixon Library Reunion

POW Mike McGrath

demonstrated how prisoners tapped on the wall to communicate

as he stands in a replica of cells at the Hanoi Hilton camp while touring the

CAPTURED:

Shot Down in Vietnam exhibit at the Richard Nixon Presidential Library as they

celebrate

the 50th anniversary of the return of the Vietnam POWs in Yorba Linda, CA,

Today, the DPAA is focused on the research, investigation,

recovery, and identification

of the approximately 34,000 (out of approximately 83,000 missing DoD personnel)

believed to be recoverable, who were lost in conflicts

from World War II to Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Congressional funding gap slows hunt for remains

of Vietnam War dead.

By WYATT

OLSON

STARS AND

STRIPES February

28, 2024

About

81,000 Americans are still missing from World War II, the Korean War, the

Vietnam War,

the Cold War and Gulf Wars, according to DPAA. Almost 90% of those are from

World War II.

About 41,000 are presumed lost at sea, making the recovery of many of them unlikely, if not impossible.

The 1,577 service members still unaccounted for from the Vietnam War, however, are the toughest cases, Byrd said.

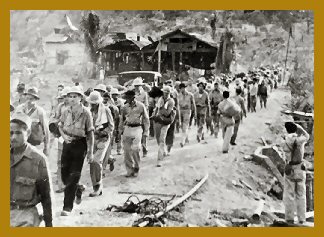

Marine Corps Staff Sgt. Joshua Alexander, left, and Navy Petty Officer 1st Class

Joshua Weber,

of the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, take part in an excavation in Quang

Binh Province, Vietnam, Feb. 26, 2023.

Marine Corps Staff Sgt. Joshua Alexander, left, and Navy Petty Officer 1st Class

Joshua Weber, of the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency,

take part in an excavation in Quang Binh Province, Vietnam, Feb. 26, 2023.

More than 2,700 prisoners were buried on the site, some of whom were identified

and reburied by the U.S. soon after the war.

U.S. service members assigned to the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency carry out

a disinterment ceremony

at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu, Hawaii, Jan. 29,

2023.

“Time is our enemy,” he said. “The footprints of battlefields have been

destroyed by progress.

The acidic soil is eating away at the remains.

Many of the veterans are passing on, along with their memories of the

battlefield.”

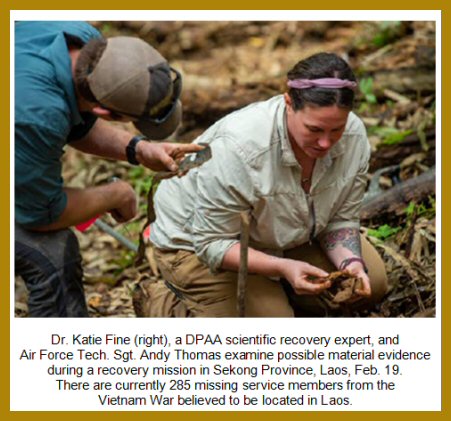

KHAMMOUANE, Laos --

With

1,586 service members missing in action from the Vietnam War, the Defense

POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) deploys hundreds of service members,

DoD civilians, and contractors all over the world in hopes of returning our

nation’s fallen heroes.

Recently a team of 59 personnel completed DPAA’s second Laos mission of fiscal

year 2017, covering the Central East region of Laos. From rice patties to

mountainsides,

the teams excavated thousands of square meters of land recovering important

evidence relating to missing servicemen lost during the war.

“I’m

very honored to have been part of this initiative to bring our missing home,”

said U.S. Navy Petty Officer 1st Class Chris Walgenbach,

recovery non-commissioned officer. “This mission has been the most unique part

of my 13 year career in the military and I know others feel the same way.”

Every

team member plays an important role in mission success. Whether that is the

recovery non-commissioned officer setting up the sites,

or the recovery leader collecting scientific data, working together ensures

nothing is overlooked and the safety of the team remains number one priority.

Due

to the efforts of the teams, Laos representatives handed over possible remains

to the U.S. to be repatriated and welcomed back on American soil after 48 years.

Upon arrival the possible remains will be transported to DPAA’s laboratory for

examination and possible identification.

“During this mission I have worked along side some of the greatest men and women

I’ve had the pleasure of meeting,

and being chosen for the repatriation ceremony was a perfect way to end such a

great mission,” said U.S. Marine Corps Cpl. Andrew Brod,

recovery non-commissioned officer. “It is truly an honor to be bringing closure

to the families of our fallen service members.”

The

hard work and continued dedication of these teams makes it possible for DPAA to

fulfill our nations promise and

provide fullest possible accounting for our missing service members to their

families and the nation.

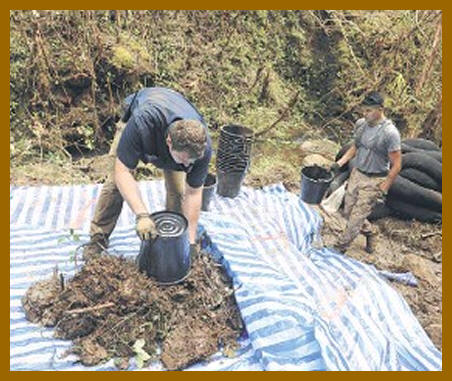

U.S. Navy

Petty Officer 1st Class Ameil Fredeluces, edic, and U.S. Marine Corps. Staff

Sgt. Eddie Ludwig, explosive ordinance disposal technician,

remove dirt from units during excavation operations as part of the Defense

POW/MIA Accounting Agency’s mission in the Khammouane Province, Laos,

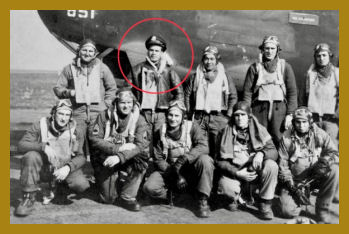

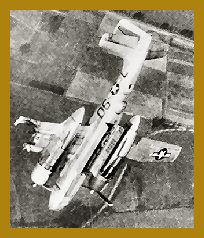

Recovery Team Three executed excavation operations in

search of two missing U.S. Air Force pilots who crashed while on a visual

reconnaissance mission during the Vietnam War over 48 years ago. DPAA’s mission

is to provide the fullest possible accounting

for our missing personnel to their families and the nation.

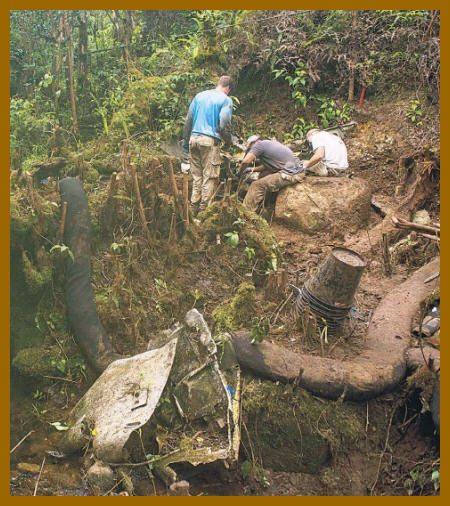

Members of

the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency dig units during excavation operations as

part of the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency’s

mission in the Khammouane Province, Laos. Recovery Team Three

executed excavation operations in search of two missing

U.S. Air Force pilots who crashed while on a visual reconnaissance mission

during the Vietnam War over 48 years ago. DPAA’s mission is to provide the

fullest possible accounting for our missing personnel to their families and the

nation.

Jack Kenkeo,

life support investigator, shovels dirt from the screening stations during

excavation operations as part of the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency’s

mission in the Khammouane Province, Laos. Recovery Team Three

executed excavation operations in search of two missing U.S. Air Force pilots

who crashed while on a visual reconnaissance mission during the Vietnam War over

48 years ago.

DPAA’s mission is to provide the fullest possible accounting for our missing

personnel to their families and the nation.

U.S. Army

Staff Sgt. Francis Sangiamvongse, linguist, screens soil with local villagers

during excavation operations as part of the Defense POW/MIA

Accounting Agency’s mission in the Khammouane Province, Laos.

Recovery Team Three executed excavation operations in search

of two missing U.S. Air Force pilots who crashed while on a visual

reconnaissance mission during the Vietnam War over 48 years ago.

DPAA’s mission is to provide the fullest possible accounting for our missing

personnel to their families and the nation.

Lynn Rakos,

scientific recovery expert, waters hard soil to help with excavation operations

as part of the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency’s mission

in the Khammovan Province, Laos. Recovery Team three executed

excavation operations in search of two missing U.S. Air Force pilots

who crashed while on a visual reconnaissance mission during the Vietnam War over

48 years ago.

DPAA’s mission is to provide the fullest possible accounting for our missing

personnel to their families and the nation.

Making the effort to thank the troops for what they do out in the field

means everything.

With a DPAA recovery team in Quang Nam Province, two hours west of Da Nang,

Vietnam.

The UW-Madison

story involved

a group of six students and staff members who were part of a team that unearthed

a World War II U.S. fighter aircraft—

and possibly remains of its pilot—in the ground under a farm field in France

this summer.

The team used ground-penetrating radar and a photo taken by a

British reconnaissance plane two days after the May, 1944

crash of the P-47 Thunderbolt flown by 1st Lt. Frank Fazekas.

Search underway for Lakewood, Ohio airman of World War II

Search underway for Lakewood, Ohio airman of World War II.

Divers of the U.S. Defense

POW/MIA

Accounting Agency and Civil Defense of Grado, Italy,

prepare for an exploratory dive on the sunken B-24 bomber.

This B-24 Liberator is the same type of airplane that

Lakewood, Ohio airman Thomas McGraw was flying in when it was shot down and

crashed off the coast of Italy during World War II.

A Missing Air Crew Report details the last flight of the B-24 and nose gunner

Thomas McGraw of Lakewood, Ohio.

B-24 located in Adriatic; Crewmanis bones sought Ught Lakewood Manis remains

crewman Omber crew,am2-2k-28 bold Header from A1.

A skull fragment was recovered at the site of a wrecked B-24 bomber

off the coast of Italy that may contain the remains of

Thomas McGraw,

of Lakewood, Ohio.

An underwater view of the crash site of a B-24 off Grado, Italy.

FINDING ENSIGN HAROLD P. DeMOSS IN THE MUCK AND MIRE

“Seeing

those photos was so overwhelming that I cried like a baby”

said DeMoss’ niece, Judy Ivey. “To see this actually taking place

is not anything I ever really expected.”

Anine-person military team

has been digging up mud four days a week

in the Koolau range in search of a missing World War II pilot whose

fighter crashed in cloud cover during a night training flight.

A bucket-and-pulley system

was set up to move excavated

material to a spot where it can be bundled in tarps for

helicopter transport to Wheeler Army Airfield.

NOTE: The Navy’s Bureau of Medicine and Surgery said in a 1948 letter

to the family that “an attempt to recover the remains was

considered impracticable” because the site was 7 miles

from a traveled highway in the mountains.

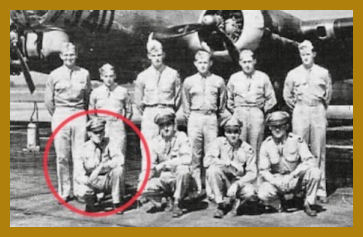

On Feb. 25, 1944, Duran wasn’t supposed to be on the doomed B-24H

Liberator, nicknamed “Knock it Off.”

Normally a nose turret gunner, Duran was the substitute tail turret gunner on

the flight, replacing the usual tail gunner who had frostbite.

The earth by the headstone next to the church in this tiny mountain village was full of rocks.

Two days of digging under a hot sun had yielded buckets of

gravel, stones the size of men’s fists and many piles of dirt – but no bones.

After 73 years, Sgt. Alfonso O. Duran was still missing.

The family feels a sense of closure regardless of the outcome,

Duran said.

“What a difference it would have made to my father and to my aunt,”

she said, “to know he had died and somebody had buried him and tended the

grave.”

Members of

the recovery team attach a POW flag to the wreckage of the

Tulsamerican, a B-24 Liberator piloted by, Lt. Eugene P. Ford, a Derry Township,

Pa. native,

when it crashed into the Adriatic Sea in 1944.

FIELD OPERATIONS IN LAOS AND CAMBODIA

US Ambassador to

Cambodia Patrick Murphy,

prepares to screen dirt during a DPAA recovery mission in Ratanakiri Province,

Cambodia, February 1, 2020.

Mr. Alexander

Garcia-Putnam, right, a senior recovery expert assigned to DPAA,

speaks to US service members and Lao officials during a joint field activity

(JFA) in Khammouan Province, Laos, February 2, 2020

SG Carter Caraker,

USA, a DPAA supply non-commissioned officer,

passes buckets to local workers during a JFA in Khammouan Province, Laos,

February 10, 2020.

During the JFA, a group of more than 70 personnel, assigned to DPAA and

augmented from military units around the globe,

worked together to help fulfill our nation's promise to provide the fullest

possible accounting of our missing personnel.

Recoveries

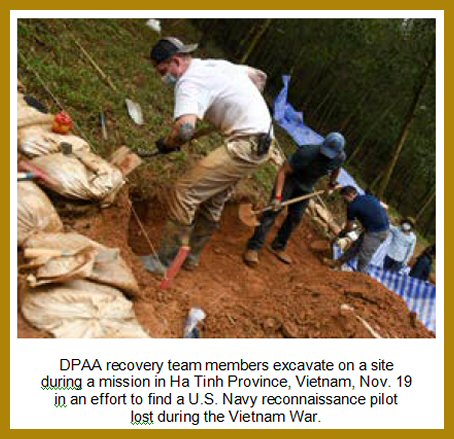

Underwater Recovery Mission - Vietnam:

U.S. Coast Guard underwater recovery mission in

Nha Trang, Khanh Hoa Province, Vietnam, May 27 2021.

Vietnam Recovery Mission:

U.S. Army DPAA recovery team member, swings a pick axe to loosen dirt during

a recovery mission in Quang Binh province, Vietnam, July 3, 2021.

Vietnam Repatriation Ceremony:

Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency Detachment 2 and the Vietnam Office for

Seeking

Missing Persons (VNOSMP) held the 155th Repatriation

Ceremony on 9 July 2021 at Gia Lam Airport outside Hanoi, Vietnam.

Repatriation Ceremony – Laos:

Detachment Three-Laos, pause for a photo during the signing of remains turnover

documents

at a Repatriation Ceremony June 22, 2021 in Vientiane, Laos.

Honorable Carry from Laos:

DPAA members conducted an Honorable Carry ceremony on Joint Base Pearl Harbor

Hickam, June 23, 2021.

The remains were recently repatriated to the U.S. during a ceremony in

Vientiane, Laos.

USS Arizona was

a Pennsylvania-class battleship built

for and by the United

States Navy in

the mid-1910s. Named in honor of the 48th

state's

recent admission into the union, the ship was the second and last of the Pennsylvania class

of "super-dreadnought"

battleships. Although commissioned in

1916, the ship remained stateside during World

War I.

Shortly after the end of the war, Arizona was

one of a number of American ships that briefly escorted President Woodrow

Wilson to

the Paris

Peace Conference.

The ship was sent to Turkey in 1919 at the beginning of the Greco-Turkish

War to

represent American interests for several months. Several years later, she was

transferred to the Pacific

Fleet and

remained there for the rest of her career.

Aside from a comprehensive modernization in 1929–31, Arizona was

regularly used for training exercises between the wars, including the annual Fleet

Problems

(training exercises). When an earthquake struck

Long Beach, California,

in 1933, Arizona's

crew provided aid to the survivors. Two years later, the ship was featured in a Jimmy

Cagney film, Here

Comes the Navy,

about the romantic troubles of a sailor. In April 1940, she and the rest of the

Pacific Fleet were transferred from California to Pearl

Harbor,

Hawaii, as a deterrent to Japanese

imperialism.

During the Japanese

attack on Pearl Harbor on

7 December 1941, Arizona was

bombed. After a bomb detonated in a powder magazine, the battleship exploded

violently and sank, killing 1,177 officers and crewmen. Unlike many of the other

ships sunk or damaged that day, Arizona was

irreparably damaged by the force of the magazine explosion, though the Navy

removed parts of the ship for reuse. The wreck still

lies at the bottom of Pearl Harbor and the USS Arizona Memorial,

dedicated on 30 May 1962 to all those who died during the attack, straddles the

ship's hull.

A number of other boats were sunk in the attack, but later

recovered and repaired.

The USS California (BB-44)

lost 100 crew members that morning, after the ship suffered extensive flooding

damage when hit by two torpedoes on the port side.

Both torpedoes detonated below the armor belt causing virtually identical damage

each time.

A 250 kg bomb also entered the starboard upper deck level, which passed through

the main deck and exploded on the armored second deck,

setting off an anti-aircraft ammunition magazine and killing about 50 men.

After three days of flooding, the California settled

into the mud with only her superstructure remaining above the surface.

She was later re-floated and dry-docked at Pearl Harbor for repairs. USS California served

many missions throughout the war,

and was eventually decommissioned in February, 1947.

![]()

On the morning of December 7, 1941, Japanese bombs fell and

torpedoes slashed through the waters of Pearl Harbor,

causing a devastating amount of damage to the vessels lined up in Battleship Row

in in the dry docks nearby.

Each of the seven battleships moored there suffered some degree of damage, some

far worse than others.

The USS Arizona (BB-39)

and the USS Oklahoma (BB-37)

were completely destroyed. Though the Maryland (BB-46)

was believed by Japan to also have been sunk, she ultimately survived and became

one of the first ships to return to the war.

During the attack on Pearl Harbor, ships like the USS Cassin (DD-372),

a Mahan-class

destroyer, suffered what was originally thought to be fatal damage.

While she was extensively damaged during the attack, she was resurrected and

went on to return to service during the remainder of World War II.

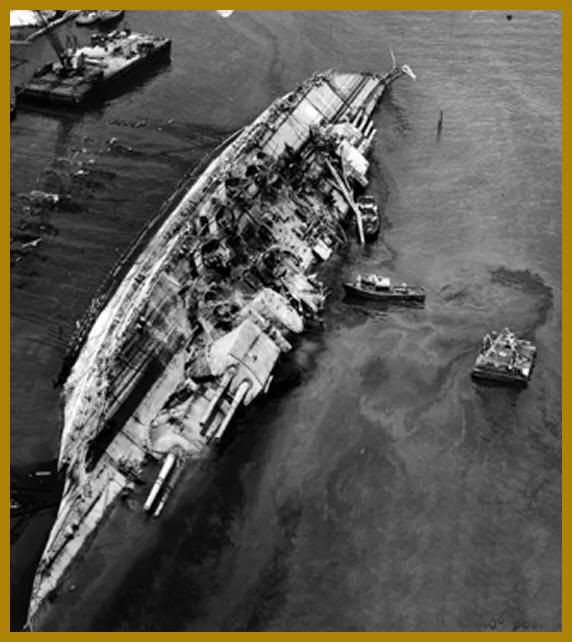

The sunken battleship USS West Virginia (BB-48) at Pearl Harbor after her fires

were out, possibly on 8 December 1941.

USS Tennessee (BB-43) is inboard. A Vought OS2U Kingfisher floatplane (marked

“4-O-3”) is upside down on West Virginia’s main deck.

A second OS2U is partially burned out atop the Turret No. 3 catapult.

In the aftermath of the attacks on Pearl Harbor during World War Two stories emerged of sailors who were trapped in the sunken battleships, some even survived for weeks.

Those who were trapped underwater banged continuously on the side of the ship so

that anyone would hear them and come to their rescue.

When the noises were first heard many thought it was just loose wreckage or part

of the clean-up operation for the destroyed harbor.

However the day after the attack, crewmen realized that there was an eerie banging noise coming from the forward hull of the USS West Virginia, which had sunk in the harbor.

t didn’t take long for the crew and Marines based at the harbor to realize that

there was nothing they could do. They could not get to these trapped sailors in

time.

Months later rescue and salvage men who raised the USS West Virginia found the

bodies of three men who had found an airlock in a storeroom but had eventually

run out of air.

Survivors say that no one wanted to go on guard duty anywhere near the USS West

Virginia since they would hear the banging of trapped survivors all night long,

but with nothing that could be done.

When salvage crews raised the battleship West Virginia six months after the

Pearl Harbor attacks,

they found the bodies of three sailors huddled in an airtight storeroom —

and a calendar on which 16 days had been crossed off in

red pencil.

The USS Oklahoma was on Battleship Row in Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. That was the morning that the Japanese Empire attacked the United States by surprise.

The Japanese

used dive–bombers, fighter–bombers, and torpedo planes to sink nine ships,

including five battleships, and severely damage 21 ships.

There were 2,402 US deaths from the attack. 1,177 of

those deaths were from the USS Arizona,

while 429 of the deaths were from the USS Oklahoma.

The crew of the USS Oklahoma did everything they could to fight back. In the first ten minutes of the battle, though, eight torpedoes hit the Oklahoma, and she began to capsize. A ninth torpedo would hit her as she sunk in the mud. 14 Marines, and 415 sailors would give their lives. 32 men were cut out through the hull while the others were beneath the waterline. Banging could be heard for over 3 days and then there was silence.

After the battle, the Navy decided that they could not salvage the Oklahoma due to how much damage she had received. The difficult savage job began in March 1943, and Oklahoma entered dry dock 28 December. Decommissioning September 1, 1944, Oklahoma was stripped of guns and superstructure, and sold December 5, 1946 to Moore Drydock Co., Oakland, Calif. Oklahoma parted her tow line and sank May 17, 1947. 540 miles out, bound from Pearl Harbor to San Francisco. Today, there is a memorial to the USS Oklahoma and the 429 sailors and marines lost on December 7, 1941, located on Ford Island in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

![]()

The minelayer Oglala technically

didn't suffer a hit on December 7, but a torpedo passed under it and hit the USS

Helena.

The blast from that crippled the old Oglala which

had been built as a civilian vessel in 1906.

The crewmembers took their guns to the Navy Yard Dock and set them up to provide

more defenses.

They also set up a first aid station that saved the lives of West Virginia

crewmembers.

The ship suffered horribly, eventually capsizing and sinking

until just a few feet of the ship's starboard side remained above water.

It was declared lost, and the Navy even considered blowing it up with dynamite

to clear the dock it had sunk next to.

But the decision was made that it could destroy the dock, so the Navy had to

refloat it. At that point, it made sense to dry dock and repair it.

None of the crew of Oglala were killed in the attack, although three received injuries.

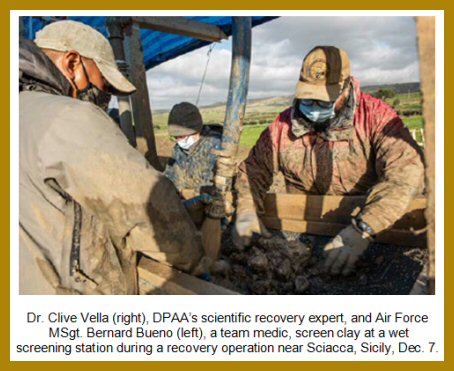

Sean Patterson, Armed Forces Medical Examiner System Department

of Defense DNA Quality Management Section DNA Analyst,

replaces U. S. Navy Fireman 1st Class Billy James Johnson's picture background,

signifying him as an identified service member who was previously missing in

action.

Johnson marks the 200th service member to be identified following the December

7, 1941 Pearl Harbor

attack where 429 U.S. Sailors and Marines were killed on the USS Oklahoma

(BB-37).

A

series of large posters hang in the conference room of the Defense POW/MIA

Accounting Agency laboratory located at Offutt Air Base, Nebraska.

The heading on each of the posters states “USS OKLAHOMA.” Underneath the

headings are neat rows of printed rectangular frames.

Each one represents a person who was unaccounted for when the USS Oklahoma was

sunk during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

Thanks

to the work of Dr. Brown’s team, the remains of 200 previously unknown crewmen

from the USS Oklahoma

have now been returned to their families for proper burial and their families

have those long-awaited answers.

The story of the USS Oklahoma’s lost crewmen is

an evolving history lesson that began on what

President Franklin D. Roosevelt called

“a date that will live in infamy.”

LIST OF USS OKLAHOMA IDENTIFICATIONS FROM MICHIGAN:

(Please note that in some USS Oklahoma identifications,

the primary next of kin has yet to be notified,

and therefore the names will not be released at this time.)

Seaman Second Class Warren P. Hickok of Kalamazoo, Mich.

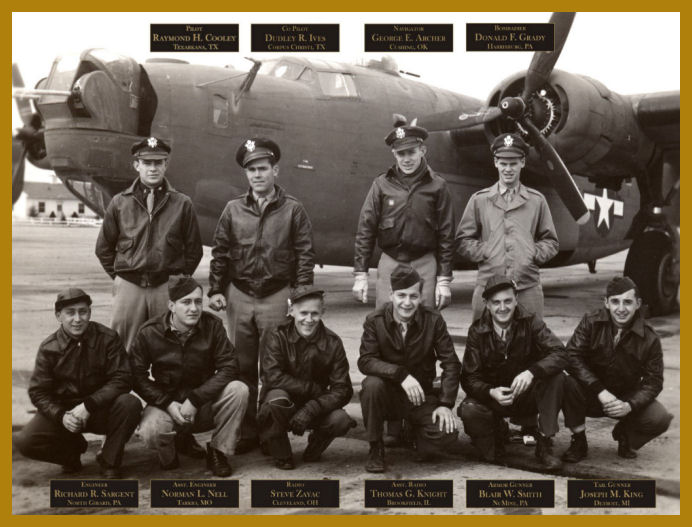

Staff Sgt. Joseph M. King, of Detroit, Mich.

Fireman Third Class Gerald G. Lehman, of Hancock, Mich.

Machinist Mate First Class Fred M. Jones, 30 of Port Huron, Michigan

Navy Fireman 2nd Class Lowell E. Valley, 19, of Ontonagon, Michigan,

Navy Seaman 1st Class Robert W. Headington, 19, Bay City, Michigan

Navy Seaman 2nd Class John C. Auld, 23, Grosse Park, Michigan,

Navy Ensign William M. Finnegan, 44, of Bessemer, Michigan,

Navy Machinist’s Mate 1st Class Fred M. Jones, 31, of Otter Lake, Michigan,

Navy Seaman 1st Class Robert W. Headington, 19, of Bay City, Michigan,

Navy Seaman 1st Class Edward Wasielewski, Plymouth, MI

U.S. Naval Reserve Ensign Frances

C. Flaherty, 22, of

Navy Seaman 1st Class Joe R. Nightingale, 20, Kalamazoo, Michigan

Navy Seaman 1st Class Edward Wasielewski, 21, of Detroit,

U.S. Naval Reserve Ensign Francis C. Flaherty, 22, of Charlotte, Michigan,

Navy Seaman 2nd Class Raymond D. Boynton, 19, Grand Rapids, MI

Navy Seaman 1st Class Wilbur F. Ballance, 20, Paw Paw, Michigan

It is through this effort that the accounting community

has been able to honor the sacrifices of the USS Oklahoma Sailors and Marines

and their families who pushed for the fullest possible accounting of their loved

ones.

Ford Island

is seen in this aerial view during the Japanese attack on Pearl harbor December

7, 1941 in Hawaii.

(The photo was taken from a Japanese plane.)

Remember

the fallen: In all, 429 people on board the

battleship were killed in the attack.

Only 35 were identified in the years immediately after.

Battleship

USS Oklahoma unturned hull at the bottom of Pearl Harbor

after the devastating Japanese bombing attack on Dec. 7, 1941.

The USS

Oklahoma, moored at Ford Island, Pearl Harbor, was sunk by

Japanese aircraft during the attack on Pearl Harbor.

A total of 429 crewmen aboard the USS Oklahoma were killed in the early morning hours of Dec.

7, 1941,

after the ship quickly capsized from the numerous torpedo hits.

![]()

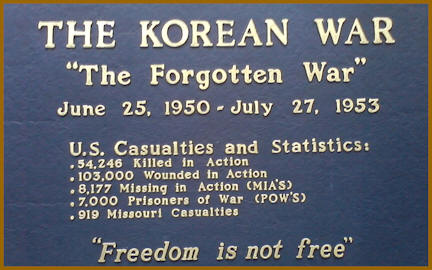

Breakdown by War - Still Unaccounted for/Unreturned Veterans:

WW I 4,422

WW II 71,970

Korea 7,438

Vietnam 1,573

Cold War 126

Gulf/Other 6

Total 85,535

*As of June 2025

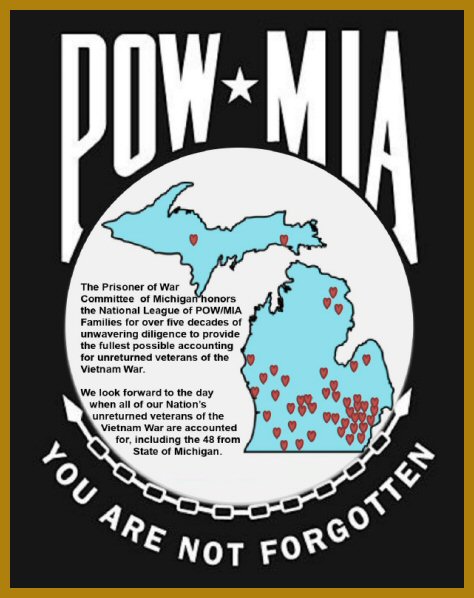

Service Personnel Not Recovered Following

WWII

from MICHIGAN - 2433

Service Personnel Not Recovered Following

Korea

from MICHIGAN - 323

Service Personnel Not Recovered Following

Cold War

from MICHIGAN - 4

Service Personnel Not Recovered Following

Viet Nam

from MICHIGAN - 48

HEROES in 2026

Airman

U.S. Army Air Forces Cpl. Joseph A. L. Richer, 24, from Maine, who was captured and died as a prisoner of war during World War II, was accounted for.

Richer was assigned to the Headquarters Squadron,

Fifth Interceptor Command, when Japanese forces invaded the Philippine Islands

in December 1941.

Intense fighting continued until the surrender of the Bataan peninsula on April

9, 1942, and of Corregidor Island on May 6, 1942.

Thousands of U.S. and Filipino service members

were captured and interned at POW camps. Richer was among those reported

captured when U.S. forces on Bataan surrendered to the Japanese.

They were subjected to the 65-mile Bataan Death

March and then held at the Cabanatuan POW Camp #1. More than 2,500 POWs perished

in this camp during the war.

According to prison camp and other historical

records, Richer died on June 30, 1942,

at the Tayabas Road work detail in the present-day province of Camarines Norte

on the Philippine Island of Luzon and was buried in the Tayabas Road camp

cemetery.

A rosette will be placed next to his name to indicate he has been accounted for.

U.S. Army Cpl. Marvin S. Patton, 20, of Cedar Bluff, Virginia, who was killed during the Korean War, was accounted for.

Patton's family recently received their full

briefing on his identification, therefore, additional details on his

identification can be shared.

In the summer of

1950, Patton was a member of Company B, 1st Battalion, 21st Infantry Regiment,

24th Infantry Division. He was reported missing in action on July 5, in the

vicinity of Osan, South Korea, where his unit was deployed to assist in halting

the Korean People’s Army advancement into South Korea.

The U.S. Army issued a presumptive finding of death for Patton on Jan. 16, 1956.In June 1951, the American Graves Registration Service Group recovered a set of remains, later designated Unknown X-1401 Tanggok, from a shallow grave less than 3 miles north of Osan.

At the time, the remains could not be positively identified and were declared

unidentifiable. In 1956, they were interred as an Unknown in the National

Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, also known as the Punchbowl, in Honolulu.

In July 2018, the

DPAA proposed a plan to disinter all 652 Korean War Unknowns from the Punchbowl.

To identify Patton’s remains,

scientists from DPAA used dental, anthropological and radio isotope analysis, as

well as chest radiograph comparison and circumstantial evidence. Additionally,

scientists from the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System used mitochondrial DNA

analysis and mitochondrial genome sequencing data.

Patton’s name is

recorded on the Courts of the Missing at the Punchbowl, along with the others

who are still missing from the Korean War.

A rosette will be placed next to his name to indicate he has been accounted for.

Patton was buried in Dublin, Virginia, on March 9, 2026.

Soldier

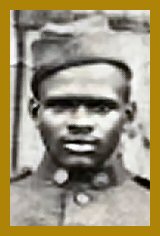

U.S. Army Pfc. St. Clair M. Gibson, 30, of New Haven, Connecticut, missing in action during World War II, was accounted for.

Gibson's family recently received their

full briefing on his identification, therefore, additional details on his

identification can be shared.

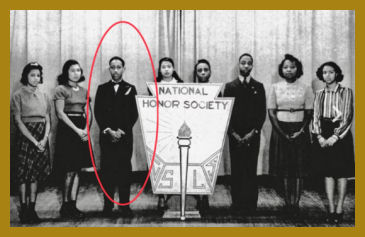

In September 1943, Gibson was assigned to Company F, 2nd Battalion, 371st

Infantry Regiment, 92nd Infantry Division.

Because the U.S. Army maintained racial segregation during the war, the 92nd Infantry Division's enlisted force was composed entirely of African American soldiers with mostly white officers. Between September 1944 and April 1945, elements of the 92nd Infantry Division were involved in heavy combat against Axis forces in northern Italy.

On Nov. 18, 1944, Gibson went missing in action during combat near Monte Canala in the northern Apennine Mountains, west of Seravezza, Italy.

His remains were not recovered. July 8, 1949, the U.S. Army Quartermaster Corps declared Gibson's remains nonrecoverable, ending all active searches for him.

As part of a comprehensive research and recovery effort focused on American soldiers missing from ground combat in Italy, DPAA researchers and scientific staff recommended exhuming the X-272 remains for new analysis. In July 2017, the Department of Defense and the American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC) disinterred the X-272 remains from Florence American Cemetery and transported them to the DPAA laboratory for forensic analysis.

To identify Gibson's remains, scientists from DPAA used dental and anthropological analysis. Additionally, scientists from the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System used mitochondrial DNA and nuclear single nucleotide polymorphism analysis.

Gibson’s name is recorded on the Tablets of the Missing at Florence American Cemetery, an American Battle Monuments Commission site in Impruneta, Italy, along with others still missing from WWII.

A rosette will be placed next to his name to indicate he has been accounted for.

Gibson will be buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia, on March 10, 2026.

Marine Corps Pfc. Norton V. Retzsch, 25, of Cincinnati, killed during World War II, was accounted for.

Retzsch's family recently received their full briefing on his identification, therefore, additional details on his identification can be shared.

In the summer of 1943, Retzsch was a member of Company C, 1st Marine Raider Battalion, 1st Marine Raider Regiment, 1st Marine Division, I Marine Amphibious Corps. He was reported missing on July 9 during the battle of Enogai on New Georgia in the Solomon Islands. He was declared non-recoverable in 1949.Following the war, the U.S. Army Quartermaster Corps’ American Graves Registration Service was charged with recovery and identification of fallen U.S. service personnel in the Pacific Theatre of Operations.

From November to December 1947, units from the 604th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company searched for Retzsch, but, after conducting a search of the Bairoko Harbor and Enogai Inlet with no results, it was recommended that the case be closed.

In December 1943, remains that had been interred at the Enogai Cemetery on New Georgia were exhumed to be moved. Two sets of Unknown remains were first reburied in the New Georgia Cemetery and then in 1945 were transferred to Finschhafen Cemetery #3 in Papua New Guinea where they were designated X-182 and X-183 Finschhafen #3.

After multiple failed attempts to positively identify both Unknowns, X-182 was buried at what is now the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial in the Philippines and X-183 was buried at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, also known as the Punchbowl, in Honolulu in 1950.

To identify Retzsch’s remains, scientists from DPAA used dental and anthropological analysis. Additionally, scientists from the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System used mitochondrial DNA analysis and mitochondrial genome sequencing data.

Retzsch’s name is recorded on the Tablets of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial in the Philippines, along with others still missing from WWII.

A rosette has been placed next to his

name to indicate he has been accounted for.

Retzsch will be buried April 13, 2026, in Marana, Arizona.

Pilot

U.S. Army Air Forces 2nd Lt. Loyst M. Towner, 24, Centralia, Washington missing in action during World War II, was accounted for.

In March 1944, Towner was assigned to the 64th

Fighter Squadron, 57th Fighter Group in Italy.

On March 24, he was piloting a P-47 Thunderbolt fighter during a dive-bombing mission with other P-47s near Civitacecchia, a coastal city northwest of Rome.

After the planes attacked the target, they were engaged by enemy aircraft. Towner was last seen at 11:15 a.m. with two enemy planes on his tail.

He never returned to base and the area in which he disappeared was under German control, so an immediate search could not be conducted.

There is no record he was ever a prisoner of war. The War Department issued a presumptive finding of death for Towner in August 1945.

Loyst M Towner is memorialized at Tablets of the Missing at Florence American Cemetery, Florence, Italy.

U.S. Army Sgt. Willis F. McNiel, 20, Parker County, Texas who was killed during the Korean War, was accounted for.

In late 1950, McNiel was a member of Company D,

1st Battalion, 32nd Infantry Regiment, 7th Infantry Division.

He was reported missing in action on Dec. 2, during a major battle near the Jangjin (Chosin) Reservoir, North Korea.

The cold weather was accompanied by frozen ground, resulting in frostbite casualties, icy roads, and weapon malfunctions.

Lacking evidence of his continued survival, the U.S. Army issued a presumptive finding of death for McNiel on Dec. 31, 1953.

Willis is remembered at the Korean War Veterans Memorial in Washington.

U.S. Army Air Forces 1st Lt. Merlin H. Reed, 27, Kansas City, Missouri killed during World War II was accounted for.

On March 9, Reed was reported Missing in Action after the B-17G Flying Fortress aircraft on which Reed was piloting was shot down north of Berlin, Germany.

Witness stated the aircraft was hit by bombs, which tore off the aircraft’s tail assembly.

Of the ten crew members onboard, two bailed out and survived, and eight were killed in the crash.

Merlin H Reed is memorialized at Tablets of the Missing at Netherlands American Cemetery, Margraten, Netherlands.

U.S. Army Air Forces Staff Sgt. Stephen J.

Fatur, 19, of Slickville, Pennsylvania,

killed during World War II, was accounted for on.

Fatur's family recently received their full

briefing on his identification, therefore, additional details on his

identification can be shared.

During World War II, Fatur was assigned to 429th

Bombardment Squadron, 2nd Bombardment Group, 15th Air Force. Fatur served as the

tailgunner aboard a B-17G “Flying Fortress” bomber. On March 22, 1945, during a

bombing mission near the village of Glinica, Poland, Fatur’s aircraft crashed.

Seven of the ten crewmembers, including Fatur, were killed. His remains were not

accounted for after the war.

Following the war, the American Graves

Registration Command searched for and disinterred the remains of U.S. servicemen

in Europe as part of the global effort to identify and return fallen servicemen

for honored burials. However, the AGRC investigations in the Soviet occupied

zone of Europe, including Poland, were severely limited

Between 2019 and 2024, DPAA partnered with Alta

Archaeological Consulting to plan and conduct five excavations at the site where

Fatur’s aircraft crashed. During the excavations, teams led by Alta recovered

possible remains, which were transferred to the DPAA Laboratory for scientific

analysis.

Fatur’s name is recorded in the Courts of the

Missing at the Punchbowl, along with the others who are missing from WWII.

A rosette will be placed next to his name to

indicate he has been accounted for.

Fatur will be buried in Delmont, Pennsylvania, on

a date yet to be determined.

Army Sgt. 1st Class Charles D. Eason, 32, Richland County, South Carolina killed during the Korean War, was accounted for.

In the summer of 1950, Eason was a member of Company A, 1st Battalion, 34th Infantry Regiment, 24th Infantry Division.

He was reported missing in action on Aug. 15 while fighting North Korean forces in the vicinity of Changnyong, South Korea.

He was not accounted for following the war.

This is an initial release. The complete accounting of Eason's case will be published once the family receives their full briefing.

Charles D Eason is memorialized at Courts of the Missing at the Honolulu Memorial

Charles is remembered at the Korean War Veterans Memorial in Washington.

U.S. Army Air Forces Pfc. Weber S. Underwood, 25, from Kentucky, who was captured and died as a prisoner of war during World War II, was accounted for.

In 1941, Underwood was a member of 28th Materiel Squadron, 20th Air Base Group, when Japanese forces invaded the Philippine Islands in December.

Intense fighting continued until the surrender of the Bataan peninsula on April 9, 1942, and of Corregidor Island on May 6, 1942.

Thousands of U.S. and Filipino service members were captured and interned at POW camps.

Underwood was among those reported captured when U.S. forces in Bataan surrendered to the Japanese.

They were subjected to the 65-mile Bataan Death March and then held at the Cabanatuan POW Camp #1. More than 2,500 POWs perished in this camp during the war.

According to prison camp

and other historical records, Underwood died June 3, 1942,

at the Tayabas Road work detail in the present-day province of Camarines

Norte on the Philippine Island of Luzon

and was buried in the Tayabas Road camp cemetery.

A rosette will be placed next to his name to indicate he has been accounted for.

U.S. Army Cpl. Byron F. Beard, Jr., 23, Scott County, Virginia, who was captured and died as a prisoner of war during World War II, was accounted for.

In 1941, Beard was a member of 409th Signal Company, Aviation, when Japanese forces invaded the Philippine Islands in December.

Intense fighting continued until the surrender of the Bataan peninsula on April 9, 1942, and of Corregidor Island on May 6, 1942.

Thousands of U.S. and Filipino service members were captured and interned at POW camps.

Beard was among those reported captured when U.S. forces in Bataan surrendered to the Japanese. They were subjected to the 65-mile Bataan Death March and then held at the Cabanatuan POW Camp #1.

More than 2,500 POWs perished in this camp during the war.

According to prison camp and other historical records, Beard died July 22, 1942, at the Tayabas Road work detail in the present-day province of Camarines Norte on the Philippine Island of Luzon and was buried in the Tayabas Road camp cemetery.

A rosette will be placed next to his name to indicate he has been accounted for.

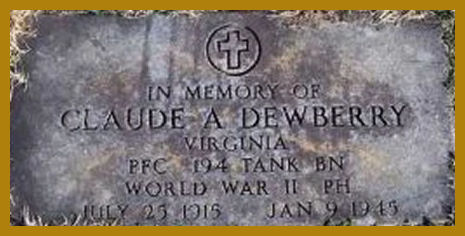

U.S. Army Pvt. Ira Warren, 26, of Seth, West Virginia, who was captured and died as a prisoner of war during World War II, was accounted for.

Warren's family recently received their full briefing on his identification, therefore, additional details on his identification can be shared.

In late 1942, Warren was a member of Headquarters Company, 194th Tank Battalion, when Japanese forces invaded the Philippine Islands in December. Intense fighting continued until the surrender of the Bataan peninsula on April 9, 1942, and of Corregidor Island on May 6, 1942.Thousands of U.S. and Filipino service members were captured and interned at POW camps.

Warren was among those reported captured when U.S. forces in Bataan surrendered to the Japanese.

They were subjected to the 65-mile Bataan Death March and then held at the Cabanatuan POW camp. More than 2,500 POWs perished in this camp during the war.

According to prison camp and other historical records, Warren died July 19, 1942, and was buried along with other deceased prisoners in the local Cabanatuan Camp Cemetery in Common Grave 312.Following the war, American Graves Registration Service personnel recovered 40 sets of remains buried in Common Grave 312.

To identify Warren’s remains, scientists from DPAA used dental, anthropological, and isotope analysis, as well as circumstantial evidence. Additionally, scientists from the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System used mitochondrial and Y-chromosome DNA analysis, as well as mitochondrial genome sequencing data.

Although interred as an Unknown in MACM, Warren’s grave was meticulously cared for over the past 70 years by the American Battle Monuments Commission.

Warren will be buried in Bloomingrose, West Virginia, in Spring 2026

U.S. Army Staff Sgt. Paul A. Gregg, 29, of Arthur, Illinois, killed during World War II, was accounted for.

Gregg's family recently received their full briefing on his identification, therefore, additional details on his identification can be shared.

In late 1944, Gregg was assigned to Company H, 2d Battalion, 109th Infantry Regiment, 28th Infantry Division. On Dec. 18, Gregg was reported missing in action following combat near Fouhren, Luxembourg, during the Battle of the Bulge.

His remains were not accounted for after the war and on Dec. 19, 1945, Army officials issued a presumptive finding of death.

In April 1945, graves registration personnel recovered one set of Unknown remains from an isolated field grave in the vicinity of Fouhren.

The remains were transferred to the United States Military Cemetery at Foy, Belgium, and processed as X-114. Despite their efforts, technicians from the American Graves Registration Command were unable to identify the X-114 remains and eventually interred them as an Unknown American soldier at Henri-Chapelle American Cemetery, an American Battle Monuments Commission site in Belgium.

To identify Gregg’s remains, scientists from DPAA used dental and anthropological analysis, as well as circumstantial evidence. Additionally, scientists from the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System used mitochondrial DNA analysis.

Gregg’s name is recorded on the Walls of the Missing at Luxembourg American Cemetery in Hamm, Luxembourg, along with others still missing from WWII.

A rosette will be placed next to his name to indicate he has been accounted for.

Gregg will be buried in Arcola, Illinois on a date yet to be determined.

U.S. Army Lt. Col. Louis E. Roemer, 43, of

Wilmington, Delaware,

Roemer's family recently received their full briefing on his identification, therefore, additional details on his identification can be shared.

In early 1942, Roemer was assigned to Chemical Warfare Service, U.S. Army Forces in the Far East on the Bataan Peninsula, in the Philippines. He was captured and held as a prisoner of war by the Empire of Japan in the Philippines until 1945 when the Japanese military moved POWs to Manila for transport to Japan aboard the transport ship Oryoku Maru.

Unaware the allied POWs were on board, a U.S. carrier-borne aircraft attacked the Oryoku Maru, which eventually sank in Subic Bay. Roemer was then transported to Takao, Formosa, known today as Taiwan, aboard the Enoura Maru.

The Japanese reported that, after U.S. forces attacked and sank the Enoura Maru, Roemer was placed aboard the Brazil Maru, bound for Moji, Fukuoka Prefecture, Japan. On Jan. 22, 1945, during the last stage of transport, Roemer reportedly died of acute colitis. However, since historical and contemporary evidence indicate that the Japanese government-reported Brazil Maru casualties list contains errors, he conceivably could have died at any point during this December 1944 to January 1945 POW transport, including the Jan. 9 attack on the Enoura Maru.

Following the end of the war, the American Graves Registration Command was tasked with investigating and recovering missing American personnel. In May 1946, AGRC Search and Recovery Team #9 exhumed a mass grave on a beach at Takao, Formosa, recovering 311 bodies. Following unsuccessful attempts to identify the remains, they were declared unidentifiable. They were buried in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, known as the Punchbowl, in Honolulu.

Between October 2022 and July 2023, DPAA disinterred Unknowns from the Punchbowl linked to the Enoura Maru. The remains were accessioned into the DPAA Laboratory for further analysis.

To identify Roemer’s remains, scientists from DPAA used dental and anthropological analysis, as well as circumstantial evidence. Additionally, scientists from the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System used mitochondrial, Y-chromosome and autosomal DNA analysis.

Roemer’s name is recorded on the Walls of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial in the Philippines, along with the others still missing from World War II.

A rosette will be placed next to his name to indicate he has been accounted for.

Roemer will be buried in Pittsburgh on a date yet to be determined.

Airman

U.S. Army Air Forces Staff Sgt. Nicholas J. Governale, 22, of Brooklyn, New York, killed during World War II, was accounted for.

Governale's family recently received their full briefing on his identification, therefore, additional details on his identification can be shared.

In the summer of 1943, Governale was a member of 69th Bombardment Squadron, 42d Bombardment Group (Medium). He was killed on July 10 when his North American B-25C-1 Mitchell medium bomber crashed on takeoff from Carney Field, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands.

His remains were not recovered after the war, and he was declared nonrecoverable on May 11, 1949.

In 2017, Project Recover, a DPAA partner, conducted an investigation in the Solomon Islands and located aircraft wreckage consistent with a B-25 in close proximity to Governale’s reported crash location.

In 2022, after receiving the data from Project Recover, historians and archaeologists at DPAA began excavating the site. The team recovered possible human remains, osseous material, possible osseous material, and material evidence, including life support equipment. Excavations continued until 2024, and all evidence recovered was accessioned into the DPAA Laboratory for analysis.

To identify Governale’s remains, scientists from DPAA used dental and anthropological analysis, as well as material evidence. Additionally, scientists from the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System used mitochondrial, Y-chromosome, and autosomal DNA analysis.

Governale’s name is recorded on the Walls of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial in the Philippines, along with the others who are still missing from World War II.

A rosette will be placed next to his name to indicate he has been accounted for.

Governale will be buried in Ridgewood, New York on a date yet to be determined.

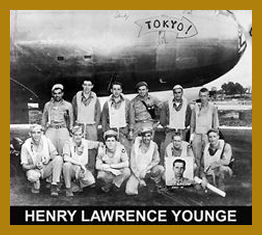

Airman

U.S. Army Air Forces Staff Sgt. Chester

A. Johnson Jr., 20, of Houston, Texas,

Johnson's family recently received their full briefing on his identification, therefore, additional details on his identification can be shared.

In the spring of 1945, Johnson served as a radio operator aboard a Boeing B-29 "Superfortress" bomber assigned to 878th Bombardment Squadron, 499th Bombardment Group (Very Heavy).

On April 14, during a combat mission to Tokyo, Japan, the aircraft was shot down over Chiba Prefecture. Johnson survived the crash but was held as a prisoner of war.

He perished in the Tokyo Military Prison during a fire on May 26, 1945.

Following the end of the war, the American Graves Registration Service was tasked with investigating and recovering missing American personnel in the Pacific Theater. Although the AGRS recovered 65 sets of remains from the Tokyo Military Prison, they were unable to identify any as Johsnon.

At the end of AGRS identification efforts, U.S. forces interred 39 Unknowns associated with the Tokyo Military Prison in Fort McKinley Cemetery, now the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial in Manila, Republic of the Philippines.

In March and April 2022, DPAA exhumed the 39 Unknowns associated with the Tokyo Prison Fire for comparison to associated casualties, including Johnson, and accessioned them into the DPAA laboratory for analysis.

To identify Johnson’s remains, scientists from DPAA used dental and anthropological analysis, as well as circumstantial evidence. Additionally, scientists from the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System used mitochondrial and Y-chromosome DNA analysis.

Johnson’s name is recorded on the Courts of the Missing at the National Cemetery of the Pacific, an American Battle Monuments Commission site in Honolulu, along with the others missing from WWII.

A rosette will be placed next to his name to indicate he has been accounted for.

Johnson will be buried in his hometown on a date yet to be determined.

U.S. Army Pvt. Condia Lynch Jr., 20, of Knoxville, Tennessee, who was captured and died as a prisoner of war during World War II, was accounted for.

Lynch's family recently received their full briefing on his identification, therefore, additional details on his identification can be shared.

In the fall of 1942, Lynch was a member of 31st Infantry Regiment, when Japanese forces invaded the Philippine Islands in December. Intense fighting continued until the surrender of the Bataan peninsula on April 9, 1942, and of Corregidor Island on May 6, 1942.

Thousands of U.S. and Filipino service members were captured and interned at POW camps. Lynch was among those reported captured when U.S. forces on Corregidor surrendered to the Japanese. He was subsequently held at the Cabanatuan POW camp. More than 2,500 POWs perished in this camp during the war.

According to prison camp and other historical records, Lynch died on June 28, 1942, and was buried along with other deceased prisoners in the local Cabanatuan Camp Cemetery in Common Grave 407.

Following the war, American Graves Registration Service (AGRS) personnel exhumed those buried at the Cabanatuan cemetery and recovered what they believed were 25 sets of remains from Common Grave 407. 17 of the sets were identified based on the presence of identification tags, leaving eight unidentified that were buried as Unknowns in the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial (MACM).

In November 2019, as part of the Cabanatuan Project, the remains associated with Common Grave 407 were disinterred from the MACM and sent to the DPAA laboratory for analysis.

To identify Lynch’s remains, scientists from DPAA used dental, anthropological, and radio isotope analysis, as well as circumstantial evidence. Additionally, scientists from the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System used mitochondrial DNA analysis, mitochondrial genome sequencing data and nuclear single nucleotide polymorphism testing.

Lynch’s grave was meticulously cared for over the past 70 years by the American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC), along with others still missing from WWII.

He is memorialized on the Walls of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery in the Philippines.

A rosette will be placed next to his name to indicate he has been accounted for.

Lynch will be buried on a date yet to be determined.

U.S. Army Staff Sgt. Dayton Polvado, 29, of Round Mountain, Texas, killed during World War II, was accounted for.

Polvado's family recently received their full briefing on his identification, therefore, additional details on his identification can be shared.

In late 1944, Polvado was assigned to Company K, 3rd Battalion, 359th Infantry Regiment, 90th Infantry Division. His battalion was engaged in combat near Pachten, Germany, when he was killed in action on Dec. 12.

His body could not be recovered due to intense fighting against heavily reinforced German forces. As American forces began to withdraw from the area, many casualties were nonrecoverable due to continued German resistance. He was not accounted for after the war.

Beginning in 1946, the American Graves Registration Command (AGRC) searched for missing American personnel in the European theater, but none of the remains found could be associated with Polvado. In 1946, an AGRC team recovered five sets of unknown, buried alongside each other in a small cemetery in Pachten, Germany.

The remains were sent to the AGRC Central Identification Point at St. Avold, France, where they were found to be comingled and consisted of six individuals. Only two were identified and the remaining four were buried as Unknowns. Polvado was declared non-recoverable.

In 2021, the Department of Defense and the American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC), exhumed the unknown remains and sent them to the DPAA laboratory for identification.

To identify Polvado’s remains, scientists from DPAA used dental and anthropological analysis as well as circumstantial evidence. Additionally, scientists from the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System used mitochondrial DNA analysis and nuclear single nucleotide polymorphism testing.

Polvado’s name is recorded on the Walls of the Missing at Lorraine American Cemetery, an American Battle Monuments Commission site in St. Avold, France, along with the others still missing from World War II.

A rosette will be placed next to his name to indicate he has been accounted for.

Polvado will be buried in his hometown on a date yet to be determined.

U.S. Army Sgt. William L. Harper, 21, of White

Sulphur Springs, West Virginia,

Harper's family recently received their full briefing on his identification, therefore, additional details on his identification can be shared.

In early 1951, Harper was a member of D Battery, 82nd Antiaircraft Artillery Automatic Weapons Battalion, 2nd Infantry Division. He was reported missing in action on Feb. 13, after the Battle of Hoengsong, South Korea.

He was captured and transported to Prisoner of War Camp 1 at Changsong, North Korea, where he died in August 1951.In 1954, during Operation Glory, North Korea unilaterally turned over remains to the United States, including one set, designated Unknown X-14238 Operation Glory. The remains were reportedly recovered from prisoner of war camps, United Nations cemeteries and isolated burial sites.

At the time, the remains could not be identified as Harper, and he was declared non-recoverable. The remains were subsequently buried as an Unknown in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, known as the Punchbowl, in Honolulu.

In July 2018, the DPAA proposed a plan to disinter 652 Korean War Unknowns from the Punchbowl. On Feb. 10, 2020, DPAA personnel disinterred Unknown X-14238 as part of Phase 2 of the Korean War Disinterment Plan and sent the remains to the DPAA laboratory for analysis.

To identify Harper’s remains, scientists from DPAA used dental, anthropological, and radio isotope analysis, as well as a chest radiograph comparison and circumstantial evidence. Additionally, scientists from the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System used mitochondrial DNA analysis, mitochondrial genome sequencing data, and nuclear single nucleotide polymorphism testing.

Harper’s name is recorded on the Courts of the Missing at the Punchbowl, along with the others who are still missing from the Korean War.

A rosette will be placed next to his name to indicate he has been accounted for.

Harper will be buried in his hometown on a date yet to be determined.

Airman

U.S. Army Air Forces Cpl. Joseph A. L. Richer, 24, Androscoggin County, Maine who was captured and died as a prisoner of war during World War II, was accounted for.

In late 1942, Richer was assigned to Headquarters Squadron, Fifth Interceptor Command, when Japanese forces invaded the Philippine Islands in December. Intense fighting continued until the surrender of the Bataan peninsula on April 9, 1942, and of Corregidor Island on May 6, 1942.

Thousands of U.S. and Filipino service members were captured and interned at POW camps.

Richer was among those reported captured when U.S. forces in Bataan surrendered to the Japanese.

They were subjected to the 65-mile Bataan Death March and then held at the Cabanatuan POW Camp #1. More than 2,500 POWs perished in this camp during the war.

According to prison camp and other historical records, Richer died on June 30, 1942, at the Tayabas Road work detail in the present-day province of Camarines Norte on the Philippine Island of Luzon and was buried in the Tayabas Road camp cemetery.

Joseph A L Richer is memorialized at Tablets of the Missing at Manila American Cemetery, Manila, Philippines.

U.S. Army Pfc. Otmer F. Hodges, Jr., 20, from Kanawha County, West Virginia killed during the Korean War, was accounted for.

In the summer of 1950, Hodges was a member of Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 2nd Battalion, 19th Infantry Regiment, 24th Infantry Division, Eighth U.S. Army. He was reportedly killed in action on July 31 after being struck by enemy machinegun fire near Chinju, Republic of Korea (South Korea). His remains were not recovered following the battle and on Jan. 16, 1956, Hodges was declared nonrecoverable.

Private First Class Hodges is memorialized on the Courts of the Missing at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific.

His name is also inscribed on the Korean War Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington, DC,

U.S. Army 1st Lt. Thomas W. Frutiger, 33

U.S. Army 1st Lt. Thomas W. Frutiger, 33,

from

Red Lion,

Pennsylvania

In 1942, Frutiger was assigned to 454th Ordnance Company on the Bataan Peninsula in the Philippines.

He was held as a prisoner of war by the Empire of Japan in the Philippines from 1942 to 1944 when the Japanese military moved POWs to Manila for transport to Japan aboard the transport ship Oryoku Maru.

Unaware the allied POWs were on board, a U.S. carrier-borne aircraft attacked the Oryoku Maru, which eventually sank in Subic Bay.

Frutiger was then transported to Takao, Formosa, known today as Taiwan, aboard the Enoura Maru.

The Japanese reported that Frutiger was killed on Jan. 9, 1945, when U.S. forces sank the Enoura Maru.

First Lieutenant Frutiger is memorialized on the Walls of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery in the Philippines.

U.S. Army Cpl. Orestus M. Stewart, 20, Jasper, Texas, killed during the Korean War, was accounted for.

In the summer of 1950, Stewart was a member of Medical Company, 9th Infantry Regiment, 2nd Infantry Division. He was reportedly killed in action on Aug. 11 in the vicinity of Kyong-ju, Republic of Korea (South Korea), when his unit was ordered to seize control of Yonil Airfield in the eastern sector of the Pusan Perimeter. His remains were not recovered following the battle and on Jan. 16, 1956, Stewart was declared nonrecoverable.

Orestus M Stewart is memorialized at Courts of the Missing at the Honolulu Memorial.

Orestus is remembered at the Korean War Veterans Memorial in Washington.

U.S. Army Pfc. Wilbert G. Linsenbardt, 27, of Lohman, Missouri, killed during World War II, was accounted for.

Linsenbardt's family recently received their full briefing on his identification, therefore, additional details on his identification can be shared.

In the winter of 1942, Linsenbardt was assigned to Company A, 128th Infantry Regiment, 32nd Infantry Division. He was reportedly killed in action on Dec. 5, near Buna in Papua New Guinea after his unit encountered intense enemy fire. His remains were not recovered after the war, and he was declared non-recoverable in 1951.

Following the war, the American Graves Registration Service, the military unit responsible for investigating and recovering missing American personnel in the Pacific Theater, began exhuming remains from approximately 11,000 graves at the Finschhafen cemeteries and prepared them for shipment to the Central Identification Point at the Manila Mausoleum in the Philippines.

In June 1943, AGRS personnel recovered asset of remains, designated X-38 Finschhafen #2, approximately 100 yards northeast of the “Triangle,” near Buna on the Urbana Front. The remains were interred at Duropa Plantation Cemetery #1A, almost 2.5 miles away. They were later exhumed and sent to the CIP in Manila for analysis but were unable to be identified at the time.

The remains were reinterred and declared unidentifiable.

To identify Linsenbardt’s remains, scientists from DPAA used dental and anthropological analysis, as well as circumstantial evidence. Additionally, scientists from the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System used mitochondrial and autosomal DNA analysis, mitochondrial genome sequencing data, and nuclear single nucleotide polymorphism analysis.

Linsenbardt’s name is recorded on the Walls of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial, along with others still missing from WWII.

A rosette will be placed next to his name to indicate he has been accounted for.

Linsenbardt will be buried in his hometown in Spring 2026.

RECENTLY

FOUND

HEROES in 2025

Airman

U.S. Air Force Master Sgt. James H.

Calfee, 36, of Boling, Texas, who was killed during the Vietnam War,

was accounted for.

Calfee's family recently received their full briefing on his

identification, therefore, additional details on his identification can be

shared.

In 1968, Calfee and 18 other men were assigned to Lima Site 85, a tactical air navigation radar site on a remote, 5,600-foot mountain peak known as Phou Pha Thi in Houaphan Province, Laos.

In the early morning of March 11, the site was overrun by

Vietnamese commandos, causing the Americans to seek safety on a narrow ledge of

the steep mountain. A few hours later, under the protective cover of A-1

Skyraider aircraft, U.S. helicopters were able to rescue eight of the

men. Calfee and 10 other Americans were killed in action and unable to be

recovered.

A second recovery operation, in 2003, resulted in the discovery of remains which were subsequently identified as one of the missing U.S. servicemen, Tech. Sgt. Patrick L. Shannon. Since that time, JPAC evaluated the feasibility of conducting recoveries on Phou Pha Thi, but logistics and safety concerns precluded further attempts.

The remains were scientifically identified as one of the 11 missing Airmen from

this incident. In 2005, a Laotian citizen provided U.S. officials an

identification card belonging to another missing servicemember, and human

remains purportedly found at the base of Phou Pha Thi.

In 2023, DPAA personnel and members from partner

organizations discovered unexploded ordnance, incident-related materials,

possible material evidence, and possible osseus remains from the research site.

The osseus material was later identified as Sgt. David Price, one of the men

missing from Lima Site 85.

All remains and evidence were subsequently accessioned into the DPAA Laboratory for scientific analysis.

To identify Calfee’s remains, scientists from DPAA used anthropological analysis and circumstantial evidence. Additionally, scientists from the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System used mitochondrial DNA and nuclear single nucleotide polymorphism DNA analysis.

Today, Calfee is

memorialized on the Courts of the Missing at the National Cemetery of the

Pacific in Honolulu, and on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington,

D.C., (Panel 44E, Line 17).

A rosette will be placed next to his name to indicate he has been accounted for.

Calfee will be buried at Evergreen Memorial Park in Wharton, Texas, at 11 a.m. on Jan. 13, 2026.

U.S. Army Pfc. William T. Farrell, 19, of Spangler, Pennsylvania, who was killed during the Korean War, was accounted for.

Farrell's recently received their full briefing on his identification, therefore, additional details on his identification can be shared.

In late 1950, Farrell was a member of Battery C, 38th Field Artillery Battalion, 2nd Infantry Division. He was reported missing in action on Nov. 30, during the battle of Ch’ongch’on River near the town of Somin-dong, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.

In 1954, during Operation Glory, North Korea unilaterally turned over remains to the United States, including one set, designated Unknown X-14473 Operation Glory.

The remains were reportedly recovered from prisoner of war camps, United Nations cemeteries and isolated burial sites. None of the remains could be identified as Farrell and he was declared non-recoverable. The remains were subsequently buried as an Unknown in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, known as the Punchbowl, in Honolulu.

To identify Farrell’s remains, scientists from DPAA used dental anthropological, isotope analysis, as well as circumstantial evidence. Additionally, scientists from the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System used mitochondrial DNA analysis, mitochondrial genome sequencing data, and nuclear single nucleotide polymorphism testing.

Farrell’s name is recorded on the Courts of the Missing at the Punchbowl, along with the others who are still missing from the Korean War.

A rosette will be placed next to his name to indicate he has been accounted for.

Farrell will be buried on a date yet to be determined.

U.S. Army Cpl. Orestus M. Stewart, 20, Jasper County, Texas killed during the Korean War, was accounted for.

In the summer of 1950, Stewart was a member of Medical Company, 9th Infantry Regiment, 2nd Infantry Division.

He was reportedly killed in action on Aug. 11 in the vicinity of Kyong-ju, Republic of Korea (South Korea) when his unit was ordered to seize control of Yonil Airfield in the eastern sector of the Pusan Perimeter.

His remains were not recovered following the battle and on Jan. 16, 1956, Stewart was declared nonrecoverable.

A rosette will be placed next to his name to indicate he has been accounted for.

Airman

U.S. Army Air Forces Cpl. John J. Ginzl,

27, of Rhinelander, Wisconsin, died

Ginzl's family recently received their full briefing on his identification, therefore, additional details on his identification can be shared.

In 1942, Ginzl was assigned to 17th Bombardment Squadron, 27th Bombardment Group on the Bataan Peninsula, in the Philippines.

He was captured on April 9 and held as a prisoner of war by the Empire of Japan in the Philippines until 1944 when the Japanese military moved POWs to Manila for transport to Japan aboard the transport ship Oryoku Maru. Unaware the allied POWs were on board, a U.S. carrier-borne aircraft attacked the Oryoku Maru, which eventually sank in Subic Bay.

Ginzl was then transported to Takao, Formosa, known today as Taiwan, aboard the Enoura Maru. The Japanese reported that Ginzl died on Jan. 9, 1945, when U.S. forces attacked and sank the Enoura Maru.

Following the end of the war, the American Graves Registration Command was tasked with investigating and recovering missing American personnel. In May 1946, AGRC Search and Recovery Team #9 exhumed a mass grave on a beach at Takao, Formosa, recovering 311 bodies, including those designated as designated X-546A Schofield Mausoleum #1. Following unsuccessful attempts to identify the remains, they were declared unidentifiable. They were buried in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, known as the Punchbowl, in Honolulu.

Ginzl’s name is recorded on the Walls of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial in the Philippines, along with the others still missing from World War II.

A rosette will be placed next to his name to indicate he has been accounted for.

Ginzl will be buried in his hometown in May 2026.

U.S. Army Cpl. Delmont Johnston, 21, of Monmouth, Maine, who was captured and died as a prisoner of war during World War II, was accounted for.

Johnston's family recently received their full briefing on his identification, therefore, additional details on his identification can be shared.

In late 1942, Johnston was a member of 16th Bombardment Squadron, 27th Bombardment Group (Light), when Japanese forces invaded the Philippine Islands in December. Intense fighting continued until the surrender of the Bataan peninsula on April 9, 1942, and of Corregidor Island on May 6, 1942.Thousands of U.S. and Filipino service members were captured and interned at POW camps.

Pruitt was among those reported captured when U.S. forces in Bataan surrendered to the Japanese. They were subjected to the 65-mile Bataan Death March and then held at the Cabanatuan POW Camp #1. More than 2,500 POWs perished in this camp during the war.

According to prison camp and other historical records, Johnston died on Dec. 30, 1942, and was buried in the local Cabanatuan Camp Cemetery in Grave 836.

Following the war, American Graves Registration Service personnel exhumed those buried at the Cabanatuan cemetery and relocated the remains to a temporary U.S. military mausoleum near Manila. In 1948, the AGRS examined the remains in an attempt to identify them.

One set of remains was recovered from Grave 836 but could not be identified as Johnston. He was declared non-recoverable on Aug. 25, 1949.

The unidentified remains were buried at the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial as an Unknown.

DPAA also uncovered evidence of discrepancies between Grave 836 and Grave 822, and found evidence that Johnston was, in fact, buried in Grave 822.

Today, Johnston is memorialized on the Walls of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial in the Philippines.

A rosette will be placed next to his name to indicate he has been accounted for.

Johnston will be buried in Augusta, Maine, in Spring 2026.

U.S. Army Capt. Willibald C. Bianchi,

29, of New Ulm, Minnesota,

Bianchi's family recently received their full briefing on his identification, therefore, additional details on his identification can be shared.

In 1942, Bianchi served as commander of Company D, 1st Battalion, 45th Infantry Regiment, Philippine Scouts, on the Bataan Peninsula in the Philippines. On Feb. 3, he volunteered to help clear a series of Japanese machine gun nests and despite being wounded multiple times, he continued leading the attack, earning the Medal of Honor for his actions.

On April 9, he was captured and held as a prisoner of war by the Empire of Japan in the Philippines until 1944 when the Japanese military moved POWs to Manila for transport to Japan aboard the transport ship Oryoku Maru.

Unaware the allied POWs were on board, a U.S. carrier-borne aircraft attacked the Oryoku Maru, which eventually sank in Subic Bay. Bianchi was then transported to Takao, Formosa, known today as Taiwan, aboard the Enoura Maru.

The Japanese reported that Bianchi was killed on Jan. 9 when U.S. forces attacked and sank the Enoura Maru.

Following the end of the war, the American Graves Registration Command (AGRC) was tasked with investigating and recovering missing American personnel.

In May 1946, AGRC Search and Recovery Team #9 exhumed a mass grave on a beach at Takao, Formosa, recovering 311 bodies. Following unsuccessful attempts to identify the remains, they were declared unidentifiable and buried in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, also known as the Punchbowl, in Honolulu.

Bianchi’s name is recorded on the Walls of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial in the Philippines, along with the others still missing from World War II.

A rosette will be placed next to his name to indicate he has been accounted for.

Bianchi will be buried in his hometown in May 2026.

U.S. Navy Aviation Radioman 2nd Class Robert L. Cyr Jr., 19, Hartford, Connecticut killed during World War II, was accounted for.

In January 1944, Cyr was assigned to Navy Patrol Squadron 91.

DPAA historians report that on Jan. 22, 1944, Cyr and eight other crew members were on board a PBY-5 Catalina seaplane when it crashed during takeoff in the Segond Channel, New Hebrides, now the Republic of Vanuatu.

Of the nine crewmembers, three survived, four were recovered in the days following the crash, and two, including Cyr, were not recovered following the war.

Robert Louis Cyr Jr is memorialized at Tablets of the Missing at Honolulu Memorial, Honolulu, Hawaii.

Airman

U.S. Army Air Forces Staff Sgt. Irvin C. Ellingson, 25,

of Dahlen, North Dakota, Died

Ellingson's family recently received their full briefing on his identification, therefore, additional details on his identification can be shared.

In the spring of 1945, Ellingson served as a radar observer aboard a Boeing B-29 "Superfortress" bomber assigned to 878th Bombardment Squadron, 499th Bombardment Group (Very Heavy). On April 14, during a combat mission to Tokyo, Japan, the aircraft was shot down over Chiba Prefecture.

Ellingson survived the crash but was held as a prisoner of war. He perished in the Tokyo Military Prison during a fire on May 26, 1945.

Following the end of the war, the American Graves Registration Service was tasked with investigating and recovering missing American personnel in the Pacific Theater. Although the AGRS recovered 65 sets of remains from the Tokyo Military Prison, they were unable to identify any as Ellingson.

At the end of AGRS identification efforts, U.S. forces interred 39 Unknowns associated with the Tokyo Military Prison in Fort McKinley Cemetery, now the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial in Manila, Republic of the Philippines.

In March and April 2022, DPAA exhumed the 39 Unknowns associated with the Tokyo Prison Fire for comparison to associated casualties, including Ellingson, and accessioned them into the DPAA laboratory for analysis.

Ellingson’s name is recorded on the Courts of the Missing at the National Cemetery of the Pacific, an American Battle Monuments Commission site in Honolulu, along with the others missing from WWII.

A rosette will be placed next to his name to indicate he has been accounted for.

Ellingson will be buried in his hometown on June 20, 2026.

U.S. Army Cpl. Aubrey L. Gibson, 21, from McCulloch County, Texas killed during the Korean War, was accounted for.

In the Summer of 1950, Gibson was a member of Battery A, 555th Field Artillery Battalion, 5th Regimental Combat Team, Eighth U.S. Army.

He was reported missing in action on Aug. 12 in the vicinity of Pongam-ni, Republic of Korea (South Korea).

The U.S. Army changed his status to Killed in Action on March 16, 1951, after receiving evidence of his death.

Gibson was declared non recoverable on Jan. 16, 1956.

U.S. Army Pfc. Richard P. Summers, 19, of Parkersburg, West Virginia, killed during World War II, was accounted for.

Summers's family recently received their full briefing on his identification, therefore, additional details on his identification can be shared.

In early 1945, Summers was assigned to Company C, 1st Battalion, 180th Infantry Regiment, 45th Infantry Division. On Jan. 6, Summers was reportedly killed in action while his unit was on patrol near Wildenguth, France. The Germans never reported Summers as a prisoner of war, and his remains were not immediately recovered.

Between July 1947 and July 1950, the American Graves Registration Command (AGRC), the unit responsible for the search and recovery of fallen American personnel in the European Theater, searched the area around Wildenguth and recovered four Unknowns in the vicinity that were never identified.

One set of Unknowns, designated X-5571 Neuville, was recovered from the Wildenguth Forest and evacuated to U.S. Military Cemetery (USMC) Neuville-en-Condroz (Neuville), Belgium.

To identify Summers’s remains, scientists from DPAA used dental and anthropological analysis, as well as circumstantial evidence. Additionally, scientists from the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System used mitochondrial DNA analysis and nuclear single nucleotide polymorphism testing.

Summers’s name is recorded on the Walls of the Missing at Epinal American Cemetery in Dinozé, France, along with others still missing from WWII.

A rosette will be placed next to his name to indicate he has been accounted for.

Summers will be buried on a date yet to be determined.

Airman

U.S. Army Air Forces Staff Sgt. Merrill E. Brewer, 26, of Monticello, Maine killed during World War II, was accounted for.

Brewer’s family recently received their full briefing on his identification, therefore, additional details on his identification can be shared.

In the fall of 1943, Brewer served as the waist gunner aboard a B-24 Liberator bomber with 858th Bombardment Squadron, 492nd Bombardment Group, Eighth Air Force. The unit was engaged in Operation CARPETBAGGER, a series of secret missions in which several specially designated bomb groups dropped supplies, arms, equipment, leaflets, and U.S. Office of Strategic Services and French agents to resistance groups operating in northern France.